According to Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem, the inflation in Canada is being impacted by unsustainable low unemployment.

Canada added 108,000 jobs in October, while unemployment remained steady at 5.2 per cent. Tiff Macklem said recent data show the labour market is cooling, and that he remains confident that an unusually high number of job vacancies absorb some of the negative impact of higher interest rates, signals the central bank thinks its efforts to constrain inflation are working.

You can read Macklem’s full remarks below.

Good morning. It’s great to be back in Toronto to discuss an issue that matters

to everyone—the Canadian labour market. I’m particularly pleased to be on a

university campus for a speech that explores the future of workers and jobs.

And I want to thank the Public Policy Forum for inviting me to engage with

students, researchers and thought leaders on this important issue.

My Governing Council colleagues and I meet with stakeholders of all

kinds—business leaders and community groups, unions and students. And everywhere

we go, we get many of the same questions. First, people ask about inflation and

interest rates. Controlling inflation is our top priority, and I’ll get into

that today. Everyone also wants to talk about jobs and the labour market, and

three questions regularly come up: Why can’t businesses find enough workers?

Are we going into a recession, and does that mean a big rise in the

unemployment rate? And what is the Bank of Canada’s role in supporting maximum

sustainable employment?

So today I want to address these questions. I will tackle them in three

parts. First, I want to outline how inflation and the labour market are linked.

I’ll explain that returning to low and stable inflation is the best way to

achieve maximum sustainable employment. Our mandate is explicit about that.

Second, I want to highlight how the Canadian labour market was hit by COVID-19,

how it recovered and what we expect in the coming months. Finally, I want to

discuss structural changes in the labour market, such as the aging of the

population, that we’d be grappling with even if the pandemic hadn’t happened. I

will discuss what we are watching and what Canadian governments and businesses

can do to help grow the supply of labour.

OUR MANDATE

Since the Bank was founded, its mandate has been to promote the economic

and financial welfare of Canada. As we said when we renewed our monetary policy

framework last December, the Government of Canada and the Bank believe that the

best contribution monetary policy can make to the well-being of Canadians is to

deliver price stability. This is formalized with an inflation target, which is

the 2% midpoint of a 1% to 3% inflation-control range.

The Government and the Bank also agree that monetary policy should

continue to support maximum sustainable employment. We recognize that maximum

sustainable employment is not directly measurable and is determined largely by

non-monetary factors that can change through time. This reflects the reality

that maximum sustainable employment is more of a concept than a number. In

practice, knowing when we’ve reached it is difficult because we have to infer

where it is, and labour market indicators give us clear signals only when we

are well above or below it.

Finally, well-anchored inflation expectations are critical to both price

stability and maximum sustainable employment. That’s why the Government and the

Bank agree that the primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain low,

stable inflation over time.1 What I want to stress here is that maximum

sustainable employment and inflation close to the 2% target go hand in hand. If

employment is well below its maximum sustainable level, the economy is missing

jobs and incomes, and spending will be below the economy’s productive capacity.

This puts downward pressure on inflation, pushing it below the target. That’s

what happened early in the pandemic. If the economy is operating above maximum

sustainable employment, businesses won’t be able to find enough workers to keep

up with demand, putting upward pressure on prices and pushing inflation above

the target. That’s where we are today.

At almost 7%, inflation is well above our 2% target. Inflation in Canada

partly reflects global factors—sharply higher prices for many commodities and

internationally traded goods. But much of the inflation we are experiencing

reflects domestic factors—namely, excess demand in the Canadian economy. Our

economy is overheated. Job vacancies are elevated, and businesses are reporting

widespread labour shortages. Over the last six months, wage growth has

increased and broadened across the economy. The unemployment rate in June hit a

record low—and while that seems like a good thing, it is not sustainable. The

tightness in the labour market is a symptom of the general imbalance between

demand and supply that is fuelling inflation and hurting all Canadians.

Since March, we have been raising our policy interest rate to help bring

inflation back to our target. Higher interest rates will work to slow spending

and labour demand in the economy, and over time, this will relieve domestic

inflationary pressures.

We’re trying to balance the risks of over- and under-tightening monetary

policy. If we don’t raise interest rates enough, Canadians will continue to

endure high inflation, and high inflation will become entrenched, requiring

much higher interest rates and a sharper slowing in the economy to restore

price stability. If we raise interest rates too much, the economy will slow

more than it needs to, unemployment will rise considerably, and inflation will

undershoot our target. Getting the balance just right is no easy task, and I

want to explain what we’ll be watching in the labour market as we make monetary

policy decisions in the months ahead.

That starts with a look at the upheaval of the pandemic and what

Canadian workers have been through over the last two and a half years.

Deep recession, rapid recovery and excess demand

The recent history of the labour market can be broken into three

distinct phases: pandemic-related economic shutdowns, the recovery that came

with re-opening, and the current environment of excess demand. Let me address

each of these in turn.

THE PANDEMIC SHOCK

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the biggest global downturn since the Great

Depression. Much of the economy shut down to contain the spread of the virus,

and millions of people lost their jobs. In Canada, we plunged into the deepest

recession on record, and the effects were devastating. Roughly 3 million people

who were employed before the pandemic were out of work by April 2020. And

another 2.5 million were working less than half of their usual hours. The shock

hit workplaces from coast to coast to coast.

But it hit very unequally. Work that required close contact with

people—mainly in the services sector—was shut down. That disproportionately

affected youth, women and low-wage workers. The closure of schools and daycares

also hit women with young children harder, and they experienced a greater

decline in their hours worked.

Never before has so much of the economy been shut down so suddenly and

for so long. We were very concerned that it would result in scarring. In other

words, we worried that damage to the incomes and careers of a whole segment of

the population, particularly women, youth and immigrants, would be permanent.

THE RECOVERY

That brings me to the second phase: the fastest recovery ever. Do you

remember that first year of the pandemic? We couldn’t travel abroad or even

much within Canada, so we stayed home. We renovated our homes to accommodate

working and studying remotely, and we bought many goods to replace the fun we’d

normally get from the services sector.

Just four months after the employment lows of April, nearly two-thirds

of the job losses were recouped (Chart 1). What was behind the rapid bounce

back? It was largely because the recession came from an unprecedented event—the

pandemic—and not from imbalances or structural problems in the economy. That meant

that when the economy reopened, employment could be restored quickly. We

expected a rapid rebound in employment with reopening, but we were concerned

that too many people would be left behind. Fortunately, the scarring we were

worried about wasn’t as pervasive as we had feared because employment recovered

quickly.

The synchronous policy response of governments and central banks around

the world played a big role in supporting the recovery. In Canada, fiscal

policies were designed to help keep workers attached to their employers and

businesses afloat even with little money coming in.2 That limited damage

to the labour market. Monetary policy actions complemented these fiscal

policies. We cut policy interest rates and introduced quantitative easing to

reduce borrowing costs, which supported spending and helped restore employment.

The reopening of schools and daycares helped too. As schools returned to

in-class teaching, mothers went back to work. This reduced the uneven impact of

the pandemic, but it did not eliminate it.3

As the vaccination rate increased and the economy reopened, those

employed in goods-producing industries returned to work sooner than those

engaged in hard-to-distance services.4 And sectors where remote work is

effective—such as professional services, public administration and finance, and

insurance and real estate—experienced employment well above their pre-pandemic

levels, while employment in services sectors such as hotels and restaurants

remained much below.

Overall, this rapid pace of the recovery is unheard of, far faster than

in past recessions.

EXCESS DEMAND

That brings me to 2022 and our current labour market. We are in excess

demand, where the economy’s need for labour is outpacing its ability to supply

it. At the end of last year, it was not obvious that the labour market would

rapidly overheat in 2022. The Omicron variant was spreading, and COVID-19 case

numbers were once again rising. But looking through the volatility in the

labour market caused by waves of the pandemic, we can now see a clear trend of

an increasingly tight labour market in 2022. Employment growth remained strong,

reports of labour shortages increased, and wage growth picked up.

To meet rising demand, employers reached more deeply into the labour

market, and they found some new workers. Hiring of immigrants—especially recent

immigrants—increased, easing employment gaps between these workers and Canadian-born

prime-age workers.5 Pandemic innovation and strong labour markets also

brought more flexibility to some jobs, partly due to digitalization accelerated

by the pandemic. Employers could more easily accommodate workers in remote

locations or those who needed flexible hours. Long-term unemployment, which

rose sharply during the pandemic, returned to its pre-pandemic levels.

We began raising our policy interest rate in March to cool this

overheated economy, but the momentum in the labour market held. Employment

gains continued, and labour shortages intensified through the spring. The

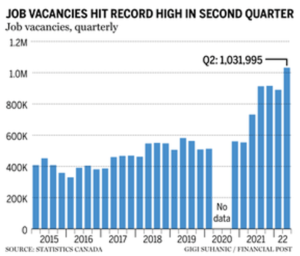

unemployment rate reached a record low 4.9% in June. Job vacancies exceeded one

million in the second quarter—a new record. Rising vacancies with low

unemployment were clear signs that the economy was out of balance, with demand

running ahead of supply.

In recent months, we’ve seen initial signs that these exceptionally

tight labour market conditions have started to ease. Since the spring,

employment has levelled off, and the unemployment rate has crept up a little,

to 5.2%. Wage growth has risen but now looks to be plateauing. Job vacancies

have started to decline. Their softening has been evident in sectors that are

more sensitive to interest rates, such as manufacturing and construction (Chart

2).

Looking ahead to balance

As we look ahead, there are two elements to achieving a better-balanced

labour market: demand and supply. Demand for labour needs to moderate so supply

can catch up. And the more the labour supply grows over time, the less slowing

is needed in labour demand to restore and maintain price stability.

Labour demand

The first part—slowing demand—is what we influence with interest rate

increases. Generally, low unemployment and high demand for workers benefit

Canada’s economy. Good jobs are the best way to reduce inequality and ensure

that Canadians have the income they need to meet the needs of their families.

But right now, we need the economy to slow down. With more modest spending

growth, the demand for labour by businesses will ease, vacancies will decline,

and the labour market will come into better balance. This will relieve price

pressures.

Increasingly, we hear concerns that Europe, the United States and even

Canada are heading for a recession. In our Business Outlook

Survey released a few weeks ago, a majority of Canadian firms surveyed

said a recession is likely in the next 12 months. As we said in our

October Monetary Policy Report, we expect growth to stall in the next few

quarters—in other words, growth will be close to zero. That means two or three

quarters of slightly negative growth are just as likely as two or three

quarters of slightly positive growth. That’s not a severe recession, but it is

a significant slowing of the economy.

Slower economic growth will likely lead to higher unemployment. We know

that job losses have a human cost. But because the labour market is so hot and

we have an exceptionally high number of vacant jobs, there is scope to cool the

labour market without causing the kind of large surge in unemployment that we

have typically experienced in recessions.

As we use higher interest rates to cool inflation, we’ll be watching

very closely for signs that the economy and the labour market are responding.

One way to explore the needed adjustment in our labour market is through the

lens of what economists call the Beveridge curve. This curve depicts the

typically inverse relationship between job vacancies and unemployment (Chart

3).

As job vacancies decline, unemployment usually goes up. But by how much?

That depends on where the labour market is along the curve. Generally speaking,

when job vacancies are high, as they are now, a decline in vacancies does not

lead to as big an increase in unemployment as it does when job vacancies are

low to begin with. Staff analysis of Canada’s Beveridge curve suggests that the

unemployment rate will rise somewhat if the job vacancy rate returns to more

normal levels. But it would not be high unemployment by historical

standards.

So what does that mean for Canadian workers? Well, it’s clear that the

adjustment is not painless. Lower vacancies mean it could take longer to find a

job, and some businesses will find that with less demand for their products,

they don’t have enough work for all their workers. But relieving the pressure

in the labour market will contribute to restoring price stability.

We’ll be watching a broad set of indicators to gauge the health of the

labour market and how it is adjusting to tighter monetary policy. As we watch

to see how the economy is responding to higher interest rates, we expect that

some parts of the economy will be more sensitive to higher borrowing costs and

will slow earlier or more sharply. The response will be somewhat uneven. Some

industries more than others will see fewer vacancies or even job losses. We’ll

be looking beyond headline employment numbers to gauge how different groups in

the labour market are adjusting. Last year, we launched our new dashboard of

indicators to help us assess the overall health of the labour market and where

we are relative to maximum sustainable employment.

LABOUR SUPPLY

That brings me to the second component of getting back to balance:

labour supply. The labour market is also being—and will continue to

be—profoundly affected by supply-side developments that are beyond the scope of

monetary policy. That brings us back to one of the frequently asked questions:

“Where are all the workers?”

The short answer is most of them are working and some have retired. We

now have half a million more people employed than we did before COVID-19 hit.

But an increase in retirements and less immigration early in the pandemic have

reduced labour force growth. That’s another reason the labour market is so

tight. These demographic shifts have played a big role in the supply of labour.

In Canada, as in many advanced economies, the age group that grew the fastest

in recent years was those aged 65 and over. That’s not pandemic-related, it’s

simply the aging of the baby boomers. Those over 65 tend to have the lowest labour

force participation rate, and that has been pulling down the growth of Canada’s

labour force in recent years.

Immigration has typically helped Canada’s labour force grow. But the

pandemic disrupted immigration flows. Borders closed, and Canada fell short of

its 2020 immigration target by about 156,000 people, or an estimated 100,000

workers.

Fortunately, immigration is bouncing back as border restrictions return

to normal. Canada met its immigration target of 401,000 in 2021. And, based on

the increase in the immigration targets since then, the shortfall in permanent

residents caused by the pandemic should be recouped in 2023.9 Many

advanced economies whose populations are aging are looking to increased

immigration to meet the needs of their labour markets. But because of

relatively higher immigration targets, Canada will have an advantage in coming

years—Canada’s population growth is expected to far exceed that of other G7

countries (Chart 4).

This is a key reason why the growth outlook in our October Monetary

Policy Report exceeds that of some of our peers, including the United

States. The strong immigration targets suggest that net immigration will

account for over two-thirds of the expected growth in Canada’s potential

output.

The strength of the labour market has helped improve outcomes for recent

immigrants. We can also increase participation by other workers, including

women, if we leverage the changes that these tight labour markets have brought.

We can further reduce the long-standing gap between prime working-age women and

men. The pandemic showed us how important child care is—when it disappeared, so

did many female workers. Canada’s female participation rate is higher than that

of the United States. But other countries have higher female participation than

we do—we’re only just above the median of member countries of the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development for participation of women aged 25 to

54, ranking 16th out of 38 in 2021. Improvements to universal child care

may narrow these differences, though the full effects will take time.

Other populations may also benefit from improved labour market access,

including Indigenous people, who have a younger and faster-growing population

than many other groups. Potential for remote work, as well as training to

develop skills in areas with critical labour shortages, may open new

opportunities for groups facing local labour market challenges. And companies

need to do their part to attract and retain new segments of the labour force.

By adjusting to and taking advantage of structural changes in the labour

market, Canada can increase the sustainable growth rate of our economy. An

aging population reduces the participation rate, and higher immigration is

becoming increasingly important for Canada’s potential growth. Changes brought

by globalization and technological change, especially digitalization, will also

continue to affect labour demand and the skills employers need. The net effect

on maximum sustainable employment is something we will be working to assess.

An increased supply of workers raises the rate the economy can grow

without generating inflationary pressures. But enhancing supply takes time. It

also creates new demand. New workers will have new incomes, and that will add

to spending in the economy. That’s why increasing supply, while valuable, is

not a substitute for using monetary policy to moderate demand and bring demand

and supply into balance.

CONCLUSION

It’s time for me to conclude.

Since the onset of COVID-19, the labour market has been in tremendous

turmoil. The pandemic caused a surge in unemployment and had a terribly uneven

impact, exacerbating the inequality already faced by women, youth and

marginalized workers. We were very concerned about widespread job losses, deep

cuts in consumer spending and, ultimately, deflation. But the recovery was

swift and across the board, with the fastest rebound in employment ever. Now

the economy has gone too far in the other direction. The economy is in excess

demand, the job market is too tight, and inflation is too high. Monetary policy

has begun to have an impact, but it will take time for the effects of higher

interest rates to spread through the economy and reduce demand and inflation.

Once we get through the slowdown, growth will pick up and our economy

can grow solidly again with healthy employment and low inflation. How much

employment growth we can achieve while maintaining low inflation will depend on

the growth of labour supply. This is the fundamental concept that maximum

sustainable employment captures. It is not maximum employment—it’s how much

employment the economy can sustain while maintaining price stability. As I said

earlier, you can’t have one without the other.

Growing maximum sustainable employment is a shared responsibility of

government, businesses and workers. Increased immigration adds potential

workers, and governments need to ensure newcomers have a smooth path into the

workforce, with credential recognition and settlement support like language and

skills training. Businesses need to invest in training so we can reduce the

skills mismatch. And workers need to invest in gaining the skills the new

economy needs.

Our priority at the Bank of Canada is to restore price stability. The

overriding imperative is to ensure that high inflation does not become

entrenched because, if that happens, nothing works well. This was the

experience of the 1970s.11 The failure to control inflation resulted in

high inflation and high unemployment. Labour strife increased as workers tried

to cope with large increases in the cost of living. And ultimately it took much

higher interest rates, and a severe recession with a large increase in

unemployment, to rein in inflation and re-anchor inflation expectations. That

is exactly what everyone wants to avoid.

That’s why we have front-loaded our interest rate increases. And that’s

why we are resolute in our commitment to return inflation to the 2% target. To

get there, we need to rebalance the labour market. This will be a difficult

adjustment. We want to do this in the best way possible for Canadian workers

and businesses. Higher interest rates will help cool spending and the demand

for labour in the economy. This will give supply time to catch up, relieving

price pressures. We will be monitoring a wide range of indicators to assess

this rebalancing and Canada’s sustainable growth rate. Canada has some

advantages that will help support our labour supply, creating more capacity for

growth.

The best contribution monetary policy can make to a healthy labour

market is to deliver price stability. With inflation and inflation expectations

well anchored on the 2% target, our economy, our workers and our businesses

will be positioned for growth and prosperity.

Thank you.

I would like to thank Mikael Khan and Corinne Luu for their help in

preparing this speech.

With files from The Canadian Press